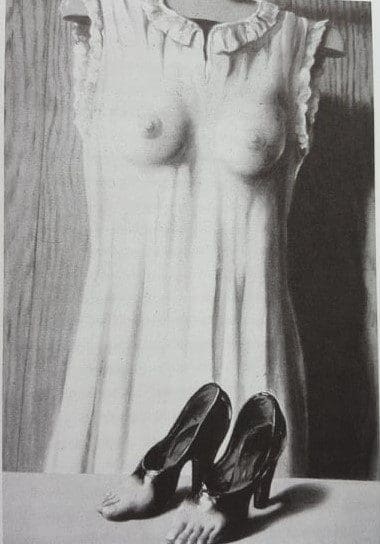

Magritte, R. (1947).La Philosophie dans le boudoir

I thought I would share a brief glimpse of the book “Fetish”, lent to me (many thanks to Judy Darragh for her kindness in this lend), containing a fantastic collection of essays published by the Princeton School of Architecture which examines fetish in terms of commodity and counterfeit as they apply to architecture and urbanism. Alongside this publication I would like to tie in some of my past and current research and, formulating a backbone to next year’s final work, the wheel of the year is turning along with my work!

From the collection of essays in Fetish this particular one caught my eye; the essay “My mother the house” by R.E. Somol (1992), honours a paper written by Manferdo Tafuri 1974 “L’Architecture dans le Boudoir: The Language of Criticism and the Criticism of Language”. Somol’s discussion around the architect in a surgical light intrigued me greatly; the architect cuts into the body of architectural structure to not perpetuate or promote, but to delve into the illusory powers or magic of particular practitioners (the magician is all smoke and mirrors). The idea that the house is the metaphor for the body is common, however I enjoyed the discussion into the “aliveness” of dwellings when they are occupied that cast my mind back to my Masters project Leitch, F. “10 Bowen St” (2008)…

Taufuir’s title refers to Rene Magritte’s La Philosophie dans le boudoir (1947). The famous work depicts the hybridization of articles of clothing in a woman’s dressing room, animating the objects and the petrification of life. However Somol doesn’t stay too long with Taufuir’s opening banter (I will be commenting on this later) but moves from the normalities of the term fetish and leans more towards the architecture ‘of granting an object a power and mystery it lacks or is feared to lack’ p.52. Somol states that this assignment may arise first in a certain kind of animalistic or anthropological discourse that purports to disclose “the secret life of buildings”, investigates “what a brick wants to be,” or even discover what is “in the nature of the materials”. Often, this attitude maintains that a building “speaks”. Together these theories and practices drape an “aura” around the architectural object, an aura – and authority – that it becomes the task of the professional artist to produce, maintain, and explore. Later in this blog I will be bringing in Ian Sinclairs London orbital in relation to the above, however it is interesting to add Sinclair’s notion of psychogeographic mapping into this discussion, where the road becomes a noose or a scar on the landscape. The road falls under the elevation of its aura towards that of “otherness”.

Somol brings into the arena the writer Vincent Scully (1974) who represents the architectural magician “par excellence” almost like an architectural ventriloquist… in his text, “The shingle style today or the historians revenge”.

Scully (1974) Pocomo Bluff Houses in Fetish p. 53

Scully (1974) Pocomo Bluff Houses in Fetish p. 53

The two new houses stand side by side on a bluff above the bay at Pocomo, with every variety of old and new shingled houses…however these two stand very much alone, and their tall vertical stance gives each of them a special quality as a person; we can emphasise with them as the embodiment of sentient beings like ourselves…like two bodies slightly turned toward each other as if in conversation…the action of people talking to each other: not now gods…but common creatures dwindling to modest human scale…The windows of each house are in tension with those of other, a family response or withdrawal. The conversation is difficult…the smaller more slender house withdraws from the other broader one. How lonely each seems. How stiff are their backs, how threatened by the elements and class systems. Scully (1974) p.53

Creatures, talking, occupied or empty, threatened, cared for, lost or found. The house itself is given an aura placing it on a human scale, almost as we see Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs; shelter, warmth food…Ferrari and or holiday home, leading into conformity to the ideal which society alludes to us we should be drawn into!

Much like Margritte’s painting discussed at the beginning encompassing aliveness/hybrid/ beyond garments, the houses are garments, we put them on as we enter, we stain them, the ego behind the elevation of the brick is us!

Somol and Taufuis dance of discussion continues beyond the above and flows into post war modernism surrounding architecture and the fetishism surrounding it, then turns towards Richard Neutra’s post war “bio-realism” in relation to the humanization of the machine. Wonderful as their discussion is, I want to bring the discussion back into the house as garment in relation to my past research.

When I under took my masters a long time ago I wrote in my abstract for my exegesis: My project was a site specific based exploration into the boundaries between the domestic home and the navigation of the anxious corporeal body (OCD) which dwells in the space. …the project explored the notions of the domestic space being formed into a container for intrusive thoughts through physical acts of decontaminating, containment, sealing and expelling the elements of dirt. The body and the home become a hybrid entity alluding to the extreme control which forms and takes over the domestic space.

Changeling Scully’s architectural ventriloquism through the description of the ‘aura’ of the two houses and their personalities and egos, activated not just through their architects surgeon-esque ways, but through the owners’ actions and interactions created through living in the dwelling (some magical, some surgical). I would like to delve into my research from my Masters (2008) in which I discuss Dorothy Arzner’s 1936 film “Craig’s Wife”, which tells of a housewife called Harriett Craig (played by Rosalind Russell), who becomes obsessed with controlling potential contamination of her domestic space and the aura she carries around which in turn rubs off onto her domestic dwelling. I found this intriguing, as along with her decontamination and control of her domestic space, is her control over her own body, aura and the way in which this is presented. I remember reading Beverly Gordons’s text (1996) Woman’s domestic Body during this time, in which she discusses the physical and physiological associations between a woman’s’ body and the domestic interior in the industrial age. Gordon suggests that in this era, the home and body were inscribed upon each other, so that the domestic space became an extension of the housewife’s aura, she suggests that the housewife dissolves into the fabric of the home, physically , emotionally and mentally; she is the surgeon and magician. This process represents the transmutation of the female into the housewife; she becomes a material of the domestic space, turning into a pillar of strength supporting the physical and emotional needs of the house. This interpretation is paralleled in Dorothy Arzners 1936 work through the similar focus on obsession and possession. Pulling back to Magritte’s (1947) work, where the hybrid of the animation of the object becomes the petrification of life, we can see the hybrid formation of the housewife being crafted and sculpted over time (a lifetime), forming an extension of “otherness” ; there is an expectation that the housewife will be obsessively focussed on the cleanliness of the domestic space. The perpetual removal by the housewife of any evidence of others ‘existence allows her to create a corporeal landscape free from external contamination. The movement causes psychogeographic mapping, the feet padded over the same floor, hollowing out journeys, like road ways, or veins pulsating with life. The work of Ian Sinclair (2002), “London orbital” describes a series of trips he took tracing the M25, Londons outer ring road; he describes it as ”mentally circling the capital forming a grim necklace” (Sinclair 2002, in Jeffries 2004 On the road). This notion taken from Sinclair’s quote in relation to the above is in the tracking of movement and the mapping of the sole description of the subjective life, or as Somol (1992) states, an ”aura of aliveness”; paring away any additional events or behaviours to reveal a path of least resistance taken by the intrusive thoughts of a dweller. To the casual observer It appears to be aimless wandering or drifting, but is in fact a way of dealing with the internal domestic environment. This creation of a corporeal landscape reflects the relationship of the housewife with her own domestic space. Alienation and isolation is the price to pay for the creation of such a relationship…or to fight a virus!

Still from “Craig’s Wife” (1936), Harriet Craig played by Rosalind Russell.

Still from “Craig’s Wife” (1936), Harriet Craig played by Rosalind Russell.

The German architect Bruno Taut’s 1924 text The new dwelling: woman as creator is compared by Bruno 2002 to the notion of the house as a dress. ‘In respect, the house is similar to clothing and, at certain level, is its very extension. Fertility and human creativity reside, now as ever in transforming things…’. Film and visual cultural scholar Bruno Giuliana in her (2007) text ”Public intimacy: Archecture and the visual arts”, discusses artists Louise Bourgeous’ image Femme-Maison (1940) which represents the female form as a hybrid with the house. When the female moves within the domestic space, she re-maps herself through the dialogue of her emotions and the space; thus the home becomes a place where a journey takes place sexually too. The house is a porous boundary leaking expressive intimate residue into the external world for all to see, turning the inside out. The privacy of the domestic space is challenged by the intrusions into the architectural body of the home, causing the inner life and inner consciousness to become exposed and revealed. Plaster is skin, wires are veins, windows and doors create openings of the body. Wear and tear and stains reveal lives lived, records of people, interactions with space, revealing traces of emotions, all connecting the material and social worlds.

Horn, R. (1974-5) Two hands Scratching both walls

Horn, R. (1974-5) Two hands Scratching both walls

Clothing (and buildings, external, internal) show stains, and wear and tear; the corporeality of the person is mapped out by the visible evidence of being worn by a human. By the same token the history of a garment is shown in a similar way to that of skin or hair; as an extension of the inner being. The garment indicates what lies beneath the surface, just as our faces, decorated with lines of life, are covered for now by our masks, as well as memory and worry, which map out the landscape of our lives. As we spend more and more time within our four walls/domestic space/dwelling, the walls can become close. I am reminded of Rebecca Horn’s work (1974-5) Two hands Scratching both walls, where Horn discusses her childhood illness and being bedridden for some time, contained, held, restrained, hidden, trapped, yet the mind would wander and begin to search subconscious worlds…The Azerbaijani artist and rug maker Faig Ahmed told to artist, Paula Cocozza in an interview in 2016 “Magic carpets: the art of Faig Ahmed’s melted and pixelated rugs”… now we would probably retreat to our phones, looking for pixelated answers to our boredom and mental/emotional states, a flying carpet to otherness, or as Somol (1992) points in relation to the domestic dwelling to create an alternative ‘”aura to aliveness”…

To conclude the above, Somol’s (1992) essay invites the reader into the world of architecture through the eyes of not just the architect but that of a practitioner, surgeon or magical. The practitioner challenges the life of the space, and its shifting frames of view point, much like a voodoo doll. The power of “otherness” is in the viewer and their own wants and needs through engagement, but along with that view is a whiff of death; the void between ideas, making their own interpretation of the object then activating the aura through the connection of memory and sentiment …the decay of wants and needs within our psyche can lead to entrapment, enclosed in a box; we scratch to get out. Do the marks and stains on our clothing and houses define us? Is this counter fetishism or a new level of “otherness”?

*

Arzner, D. (1936). Craigs Wife. In Bruno, G. (1002). Atlas of emotion: Journeys in Art Archecture. New York: Verso (p.88-89)

Giuliana, B. (2007). Public intimacy Archecture and the visual arts. London: MIT press

Jefferies, S. (2004). On the road. The guardian, Saturday April 24th 2004. Retrieved 4th October 2008

Leitch, F. (2008) 10 Bowen St. AUT

Manferdo Tafuri 1974 “L’Architecture dans le Boudoir: The Language of Criticism and the Criticism of Language”. In Somol, (1992.) My mother the House in Fetish Princeton School of architecture. p. 50.

Paula Cocozza (2016) Guardian, Magic carpets: the art of Faig Ahmed’s melted and pixelated rugs.

Scully, V. (1974). The shingle style today or the historian’s revenge. (New York: George Brailler, 1974) p.34-36.

Somol. R.E. (1992). My mother the house in in Fetish Princeton School of architecture. p. 50- 69

IMAGES:

Louise Bourgeous’ image Femme-Maison (1940) in Bruno Giuliana in her (2007). Public intimacy Archecture and the visual arts. London: MIT press

Horn R. (1974-5) https://www.bing.com/images/search?

Magritte, R. (1947) La Philosophie dans le boudoir, in Somol. R.E. (1992) My mother the house in in Fetish Princeton School of architecture. p. 50.

Scully, V. (1974). The shingle style today or the historian’s revenge. (New York: George Brailler, 1974) p.34