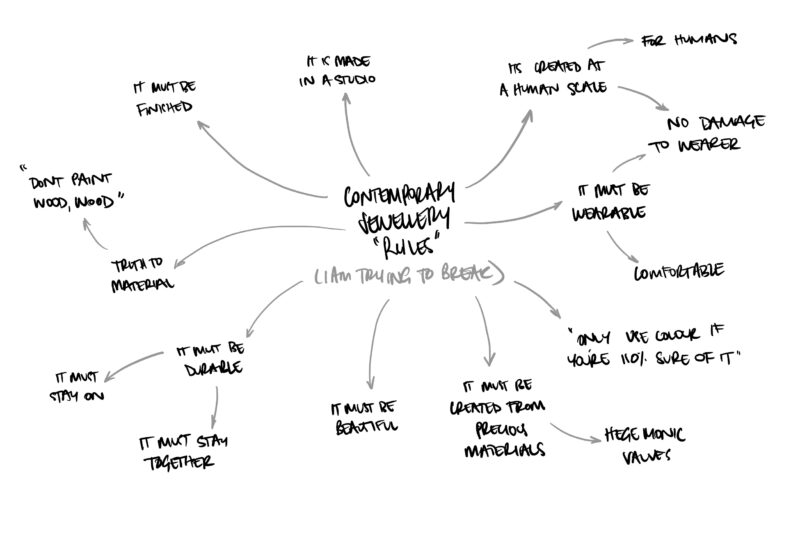

I found myself amidst the rocks and seaweed and lapping waves of Karaka Bay following a prompt from Andrea Daly in our History and Theory classes for Handshake 8. We were asked to think about the rules that surround the field of Contemporary Jewellery and in so doing we were to ponder the rules that each of us have around our individual arts practices and making processes. For me, the examination of my rules, modes and methods had really begun with the start of my handshake journey at the beginning of 2023. But this exercise revealed to me that I still have a lot of rules that are often completely unconscious, or dragged from different disciplines, from across different times and places and that have somehow continued to take hold of my practice and shape my approach to materials. Through Andrea’s provocation, I was able to bring my attention toward the unthinking and automatic choices I make in how and what I make with. Through mind maps and some deep brainstorming, I realized that my set of rules were uniquely shaped by the alchemy of gold and silversmithing, as well as my early career in architecture, but also the art practice of my mum, and the scientific modes of research demonstrated by my dad. They’re an eclectic set of rules but they command a sense of controlled process and exploration that I was keen to disrupt .

So how did my shoes get wet? Well, Andrea challenged us to make a piece of jewellery that broke our rules of course and I immediately wanted to break as many as possible. I want to make outside the studio, I wanted to be free from human scale or even having the piece be worn by people; I wanted to make something that was not durable; I wanted to create a piece that was incomplete or unfinished; I wanted to create something out of materials that weren’t classically considered to be precious; I wanted to use materials that didn’t have an detrimental impact on the environment.

And one last rule that I wanted to break was to make a piece with someone present, a kind of co-creative co-presence that would shift the way I attune to the work and pay attention to the world. On this front, I was lucky to have my dear friend and longtime collaborator, Visual Anthropologist, Viktor Baskin, visiting me in Aotearoa. We have collaborated and delved deep into ideas and philosophies of making for the duration of our decade long friendship. As an image maker and visual anthropologist, Viktor has a gift of opening different worlds for me through both the still and moving image. They generously agreed to take part by documenting the process of making and by offering a dialogue that helped to prompt and explore the emergent practice of making with and for the world outside my studio walls. An important part of this process was improvisation. It was a site-specific mode of exploration where the environment became a character in the collaboration as well. But of course, the environment is not quite so invested in the work as we perhaps were. So together, Viktor and I, were able to play and stretch the idea on the fly with both of us thinking through making, as well as responding to one another and the place itself. Often in silence, responding to one another’s movement and attention. We have both come to call this mode of exploration, ‘serious playfulness’ and we consider it the heart and soul of any experimental collaboration.

The canvas for this serious playfulness, and for the breaking of all my rules, was the deep tan sands of one of my favourite spots in Tamaki Makaurau: the headland between St Heliers and Karaka Bay. To access this place, we had to work with the moon and her tides. At high tide the shoreline disappeared and the rocks to the bay became unscalable. It was this swallowing of the tide and the restrictions it put on my body and my capacity to make something that shaped my intention to create a piece that I knew would be changed by the ocean. As the tide rose, I imagined it would claim the work and drag it dancing and tumbling into the bay. This meant that there was a time pressure to the making process but one that was unlike any other kind of time pressure that creative deadlines often generate. Here time would become material and it would become a material to work with. I also wouldn’t have time to overthink, I would have to open myself to just respond to what was there. This was a way to make and then let go of the piece in an effort to release the tight control that I feel happens in my studio space and to challenge the texture of control that rumbles through each and every one of my rules – self-imposed or otherwise.

Before we left the house, I had a collection of extremely loose ideas for what I might create but once we began to walk, talk, and make images together – Viktor and I and the bay – the bay began to gently shape my concepts into new directions. Without knowing the shape of them completely, we settled on the one flat sandy spot along the headlands, in between strata of mudstone. I realised that my previous ideas of using large bits of driftwood and rock would make for a large lasting impact on the site and our stroll over slipping rocks and cracking shells, had led me away from the impulse to add more weight to this place. Standing on the shoreline watching the clouds create shapes across the contours of Motukorea it was the white bright oyster shells shining against the damp dark sand of the shore that began to catch my eye. Slowly a resonance began to vibrate in my chest, from the sand around my feet, across the crackling bubbles in the waves, to the volcanoes around the bay in front of me.

I begin to pick up the shells without having a particular outcome in mind. At first slow, careful, almost hesitant. I’d chosen the spot for it’s almost blank canvas of sand but now I can see that there are two small rocky outcrops, covered in oyster shells that offer the chance to anchor something akin to my own volcano crater. I worked slowly to join the two with two curving line of shells. The shells telling me the ways in they’d fit together. At first a dotted line appeared, then I continued to build and make it bolder. I began to collect more quickly, my attention more honed, seeking out shapes for the gaps that were emerging. My searching and my placing began to take on their own rhythms. The placement careful – finding the shell that fits in a certain place – the search becoming a little more impatient. The sun burning through my shirt, the tide continuing to creep in behind me. Time was nudging the ocean to come and claim the piece.

As the piece came into its own, what emerged was a kind of pearl necklace made for a dormant volcano. My love for questioning the value we place on particular things and objects, on stories, places and worlds began to take shape on the sand. I wanted the offering to be ready, as much as it could be, to be taken across the sea to Motukorea.

From the moment the water touched the piece it changed. The sand divided the waves as they came towards the shore, creating watery tendrils that reached for the shells and instantly pulled them apart. They dispersed softly at first, giving over to the small rolling waves and then more violently as the shells already caught up in the waves came back to rattle the rest. The line that was once defined was now blurring. Perhaps fittingly, at this moment our memory cards filled up and our batteries ran out and the warm sun overheated the camera and we were forced to stand still, to listen, to watch and to feel the offering tumble out into the water. The waves enveloped the oyster shells. The waves that were once gentle, now crashing and taking and with no one to see but us and the birds. Slowly shapes and light began to echo one another threading relationships through the bay.

We stood mesmerized by the piece becoming movement with the water. We watched the piece declare its own energy in the waves of an unstoppable tide. Our eyes transfixed, even as we began to put our things in our bags, put our bags on our backs, our own rhythms drawn into the pull of the waves as we, slowly but surely, move our precious items up and out of the way of the incoming tide.

Our shoes were wet. The tide was changing. We had run out of time.

Acknowledgements for this offering:

Ngā mihi nui to Viktor Baskin for co-thinking, co-making and co-writing this piece with me and to Karaka Bay for collaborating with us and sharing rhythms so that we might make something together.

To see Viktor’s incredible creation from that day please follow the link here.

Above: Viktor Baskin

Above: Nellie Peoples. Image by Viktor Baskin