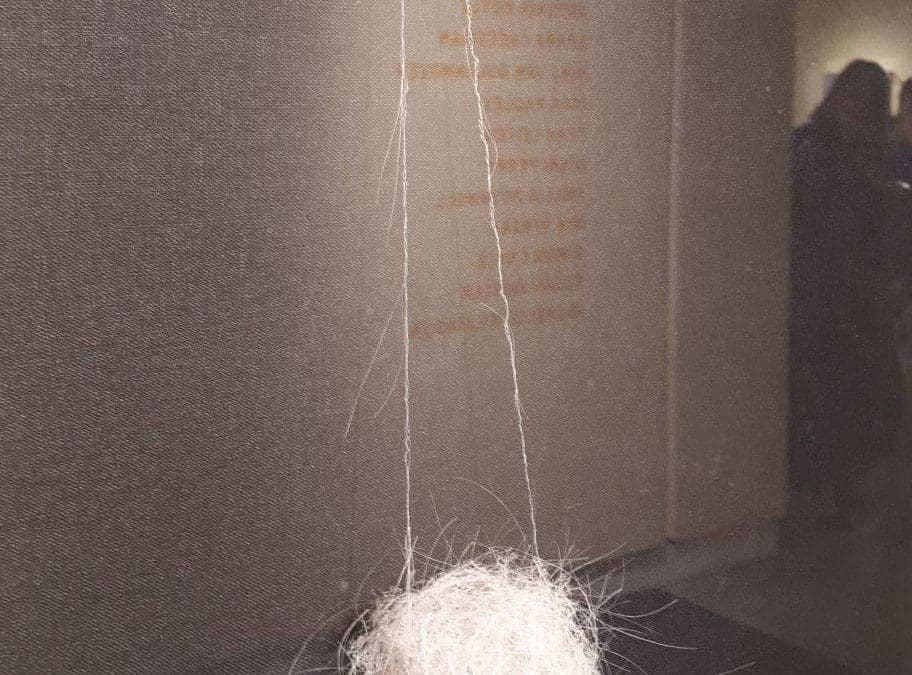

Found, given, owned, loved (April 2022) grey hair.

From DNA – some old, found, given, owned; some strands discarded from heads of long passed loved ones – a new narrative is born. The work is made from once crowning glories, now a new story; their story and my story combined! Around my neck is a faux narrative of me, another’s DNA next to my skin; holding them, extracting their knowledge, absorbing and honouring their wisdom into my body and mind…we are one! They live again!

The teaser show Glimmer ( for our end of show in August at North art Auckland) in May at Whirinaki (Upper Hutt), was a fantastic show (many thanks to curator Christina Doherty – McGregor and her wonderful team) of where our work is heading, and (personally) show casing loose ends beginning to be tied up! I found myself working with grey hair; mine, found, given, lost and loved. After reading the novel Perfume: The story of a murderer, by Patrick Suskind,( recommended to me by Iris ‘Dear you will love it, it’s right up your street!’ (if you haven’t read it, do, it’s fantastic) )… on one humid hot February day, drenched in sweat and smelling the occupants of the house… we all of a sudden stank! However it was the ideas of collecting another’s DNA, stains from the domestic arena, cataloguing them into bags or boxes and creating a new identity for one’s self… a new narrative…

Artist wearing Found, given, owned, loved ( April 2022).

Whirinaki gave the group the option to use glass/Perspex cases to display our work under. I initially chose not to (however, now I’m glad it did); I wanted my work, due to the nature of its material, to move and float slightly in the breeze as people passed, dead cells living again. This idea of movement of life after death was something I had seen at the Hellenic Museum in Melbourne back in 2016; within the collection was a the Grecian crown of the dead (also found in southern Italy where a wreath of Myrtle, a plant species that related to the deity worshipped by the family of the deceased, associated with Aphrodite, Demeter and Persephone). The wreath was a reward of eternal life after death…however as I stood and examined this exquisite object, the thunderous traffic outside made the leaves quiver in tiny springs, the air-conditioning, gave a slight sway to its delicate and fragile structure alluding to the wreath was on a person, the impression the deceased was still breathing and alive…a second life…or faux hope?!

Myrtle Wreath. Gods Myths and Mortals. Greek Treasures across the Millennia. Hellenic Museum Pub. 2016. P.66-67

For me to have the hair move and create its own energy from passers-by is a simple notion; however, it intrigued me. It was like the work wanted to float out of the gallery’s white contained space, and into society, wrapping itself around a local and going off to live with them…even when I tested the work at home it kept trying to stick to me and follow me around…some of the hair included in the work, I found upon my person after coming home from the supermarket before Christmas…whose are they? When did I pick up this residue of someone else’s DNA? These fragments of someone now living in my domestic arena!

Perspex boxes were fantastically made for our work at Whirinaki, for security, and visually it poured from the Handbag show ‘Carry me; a hundred years of handbags’ through to our show. My ideas above were altered, but still elements held; instead of just being pinned to the wall, its Perspex covering became its window into contemplation!

***

I have been delving into Victorian mourning jewellery while I gathered my hair and collected strands from all over the place. We may all be familiar with the images of lockets and mementos of this era, however it was the idea of the glass case and the domestic which has been mulling over in my mind for a while.

In my previous blogs I have discussed the domestic and movement of the dweller in their domestic space and how it’s viewed. ..also how the dweller’s residue is viewed; as dust, hair, filth!

Under glass…

I would like to start with backtracking to the blog ‘otherness’ I wrote a while back in which I discuss Giuliana Bruno’s (2002) text Atlas of Emotion: journeys in Art, architecture, and film interiors and house alongside the collected essays of the text Fetish (1992). Bruno suggests that the home can be a private museum, telling stories and travels within the space…forming affairs of the senses, they sense, and make sense of, our passing through the space (Bruno, 2002, p.105). The corporeal connection between body and dwelling shapes and morphs the internal boundaries, through movement of the body and mind, thus leaving physical and mental marks, and traces of those who have lived there. The domestic space thus becomes a private museum and a stage to be formulated and moulded into the narrative the “dweller” wishes to portray to visitors. As discussed in ‘otherness’, Dorothy Arzner’s (1936) film “Craig’s Wife” tells of a housewife called Harriet Craig who becomes obsessed with controlling potential contamination of her domestic space, despite sharing her house with her husband and maids. She also becomes obsessed with objects with surround her and is suspicious of human contact, as it reduces her to over-control the space. She becomes incorporated into the house; she is the houses’ pillar of control.

However, by looking at the placement of objects this creates a show for the public to peer at; this juxtaposes with the idea of the domestic space as a private place. Thus, the house becomes a glass case, exhibiting our lives for visitors to gauge the dwellers social and cultural status, and for the dweller to show off their goods and chattels. An example of this can be seen in American photographer Ian Goulden’s (2008) image, “The curiosity collector”.

Goulden’s, I. (2008) “The curiosity collector”

The female in the image gazes at the collection; her inclusion in the photograph places her as part of the collection. Goulden (2008) says in his artists statement the ‘she is an item to be displayed for all to peer at (Goulden, 2008, p.1). Bruno’s (2002) analogy of the dwelling acting as a container and private museum strongly parallels the Victorian idea of presenting everything under glass, thereby creating cabinets of curiosity. Lecturer and author Laurence Talairach Vielma’s (2007) text, Moulding the female body in Victoria Fairy tales and sensations Novels, discusses the Victorian admiration of the female ideas, the glass cabinet and their process of enclosing and capturing objects to be observed in silence.

Talairach-Vielmas (2007) suggests that the Victorian woman was idolised and so admired, that they were kept and treasured like dolls behind glass cases. By taking this action, the female became suffocated and isolated; finally fading away and dying through not being able to voice their own desires or fears. This notion of the female being placed and preserved behind glass brings to mind a glass tomb (the biggest being Crystal Palace by Paxton!) and the inevitable Victorian fascination with death. Talairach-Vielmas (2007) further suggestion that the Victorian female set ordinary women a standard they could never live up to…(The standards of today are not so structured; however, the media give standards which women still allude to, never being able to reach the ideal of the utopian female…I’ve touched on this in my blog ‘Magical Flying Rogg”). The Victorian female ideology was locked into the symbol of the glass coffin/case; holding the artefact in an airless stasis. As seen in the Grimm Brothers’ The glass coffin (1812) (A Tailor gets lost in the woods, spends the night in an old hut, gets carried off by a stag, and finds, behind a wall of rock opened by the stag, a beautiful maiden asleep inside a glass coffin) which parallels the Victorian feminine ideals, underlining the notions of the glass house representing femininity and death. The notion of crystallisation and preserving of the female figure is found over and over again in the Victorian period, whether as glass cases, mirrors, or windows.

The narrative of the glass coffin (1812) reveals the suffocating status of women at the time and the expectations placed on them to live up to the ideal of society. The female character is contained by a glass container. She has no means of communication through the container, but remains mute; thus she is turned into an artefact to be admired and used at whim. This containment of the female as an artefact is also suggested by American author and Lecturer Nina Auerbach in her text (1985) “Romantic imprisonment: women and other glorified outcasts”. Auerbach suggests that the female is being laid to rest, or placed in stasis, capturing her in her purest form; this stasis suppresses the ageing process, and morphs the female form into a cultural icon of the social and cultural times. ‘In her glass coffin, she is an object, to be displayed and desired….a possession, an idealised image of herself…a suppressed energy of who she once was, the glass turning her into an artefact to be admired, and covered up when not in use’ (p.41).

Whiteread, R, (2001). Monument.

When the glass coffin is empty, what then? An example of the unoccupied ‘glass coffin’ is Rachel Whiteread’s Monument (2001); the funereal aspects are preserved, but never morbid. In (2001) ‘London Calling’ David Ebony (associate managing editor of Art in America) regards Whiteread’s Monument as representing the notion of a glass coffin. Its clear glass form alludes to the qualities of transparency; the public are allowed to gaze through it, into it around it and past it; there are no concealed elements. The internal being laid bare for all to see can also be viewed in the work of Kiki Smith. She uses images of mirrored bottles in rows of 10, which bear labels in archaic lettering referencing “blood,” “Bile,” “Tears” and so on. New York critique Grace Glueck (2005) discusses Smith’s work in her article ‘An Object of practicality, from the inside and out’. Glueck sees Smith’s use of glass containers as poetic; they become spaces that are both in our world and uniquely separated from it. The containers show the internal bodily fluids are revealed, allowing the public to view the inner world of the body (much like Mona Hatoums Corps etranger, 1994). This act divorces the fluids from the body, thus creating and forming a disembodied space within the glass container and its contents. By placing the fluids into the container, the use of glass as a medium is highlighted; the contents are not only held in stasis, but are the focus of one’s view. It would be rude now to not bring into the discussion German philosopher Martin Heidegger’s notion of containment. Hubert L. Dreyfus et. Al (2000) in the text Authenticity, and Modernity, Heidegger states that contamination is ‘the limit of the enclosing body, at which it is contact with that which is enclosed’ (Dreyfus, et. al 2000, p. 215). A prime example of containment is given by Dreyfus (2000) as the example of the glass of water, in which Heidegger states the body of water in the glass is contained by the embodiment of the glass, the emptiness of the air and the surface which surrounds the glass. The filling of an empty glass container in relation to the domestic dwelling is seen in Heideggers’s essay The Thing, in Poetry, language, and Thought (2001), in which Heidegger discusses emptiness and its importance. He stresses that a jug is related to its emptiness and it is the result of its forming by the potter/maker. He believes that the ‘the vessels’s thingness does not lie at all in the material of which it consists, but in the void that holds it’ (Heidegger 2001, p.124)…an bag full of intentions?

Bag July 2020 (Fran Leitch)

The emptiness of the vessel gathers and preserves nothingness. Heidegger does not see emptiness as a failure, but as a bringing forth. The act of emptying a jug allows it to ‘contain something, into its having been freed (Heidegger 2001, p.122). The act of emptying is actually an act of creation, the perception of ‘nothingness’ actually admits and gathers.

To empty is to gather, to remove is to include…this leads me directly back to the conclusion of my last blog…we are the containers, to give and share our unconditional love; to give part of our own energy away (not in its entirety) is to gather and hold onto what you hold dearest. As the analogy of the container flows back into these past blogs, I see myself as the container of unconditional love for my family past, present, future. Emotionally and physically, the act of bleeding monthly for a woman before menopause is to empty, then to gather again, until an age where gathering people you love fills that vessels void or you are gathered and held and bound together by those who were born from the wound they are now trying to heal (see previous blog). A hair falls out, then sometimes grows back; a new stage of transcendence to otherness, and how we wish to show that ourselves, could be contained within us privately, or viewed and opened up to the public. Social media (society’s curiosity cabinet) is a prime example of where the private and public meet, and how we choose to portray ourselves…a new mask!

However, how one chooses to portray ourselves is to create our very own narrative, inside or outside of their glass case! As we turn towards the end of the HS6, I find myself working with strips of fabric, menstrual blood, rags, hair; mine, found, loved, lost, residing in the home. Empty bags I have been making throughout the Handshake which were once full of collections of hair, teeth, rags, and dust are now empty, they now only hold intentions… hang on a minute, this is all very familiar, ‘Silence [the bag} isn’t empty; its full of answers….I did a blog about that this time last year, I’ve just added more melancholy sentiment this time round!!!

***

Bibliography.

Auerbach, N. (1985). “Romantic imprisonment: women and other glorified outcasts”.New York: Columbia University Press.

Bruno, G. (2002). Atlas of Emotion: journeys in Art, architecture, and film interiors and house. New York: Verso

Dreyfus. H. et. al (2000). Authenticity, and Modernity. New York: New Press

Ebony, D. (2001). London Calling. www.artnet.com/magazine/features /ebony8-20-01

Glueck, G. (2005). An object of practically. New York Times april 1st 2005. Nytimes.com/2005/04/01/arts/design/01aldr.htm?fta=y

Heideggers, M. (2001). The Thing, in Poetry, language, and Thought . Toronto: Harper Collins.

Suskind, P. Perfume: The story of a murderer. Penguin 2008

Talairach-Vielma, L (2007). Moulding the female body in Victoria Fairy tales and sensations Novels. Boston: Ashgate Ltd

Images.

Myrtle Wreath. Gods Myths and Mortals. Greek Treasures across the Millennia. Hellenic Museum (Pub. 2016). p.66-67.

Goulden’s, I. (2008). The curiosity collector .retreaved November 2nd 2008, from farm2.static.flickr.com/1347/795617266_35c85f

Whiteread, R, (2001). Monument. Retreaved August 12th, 2008, from homepagemac.com